Are the CPGs Flying Blind with Their Advertising?

No one would willingly fly in a plane with faulty gauges. No pilot would chance a takeoff without a complete set of working instruments. And yet, the CPGs (Consumer Packaged Goods companies) seem to be flying with faulty gauges to measure their advertising.

For the last twenty-plus years, the CPGs have all been using marketing mix models (in one form or another) as the instruments to inform their advertising and promotion decisions. The promise of these models was that marketers would be able to optimize the allocation of dollars across all of the marketing tools that were available.

But where’s the growth?

Before mix modeling, product development and effective advertising built the iconic brands of the CPG companies. After decades of mix modeling use, how are CPG companies doing? Have the models led to strong, healthy and growing brands? Have advertising practices been honed to a sharper edge? Or, did the promise exceed the delivery? Let’s take a look:

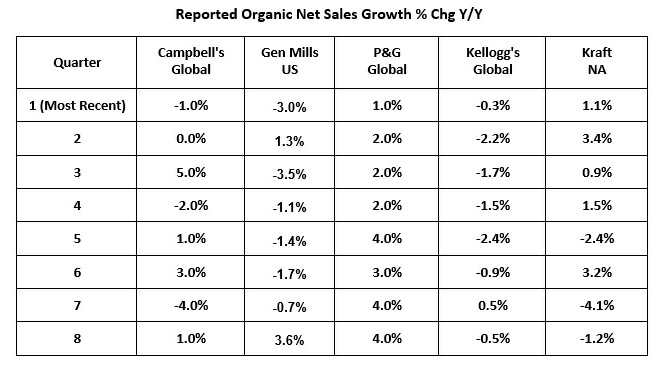

Despite spending multiple billions in advertising and promotion, these five CPGs average a dismally low 0.3% quarterly growth. The biggest of the CPGs have failed to grow, enough so that a number of CMOs/CEOs are gone, mass layoffs have occurred, P&G is jettisoning brands, and Kraft has been gobbled up by private equity.

Something has to be terribly wrong to spend so much and yet deliver so little growth. The honest question is: Could this all be wasted spending, however well optimized? And if anyone believes this spending is needed just to tread water and maintain sales volume, then we need to ask this question: What does this say about the ability of these brands to command loyalty?

Optimization on efficiency-driven ROI, not growth

During the mix modeling era the visible patterns of advertising for these companies have all looked pretty much the same: Ad budgets reduced with the money going to price promotion. The reduced budgets then led to fewer weeks on-air, the dominance of 15s over 30s, and Network Prime replaced by lowest CPM Cable. And now there’s a move to slide part of the remaining funds out of TV and into digital advertising. The rationale for all of these moves? That would be the mix models themselves.

Here’s what Erwin Ephron had to say about these kinds of changes:

“When we shift dollars from Prime to Cable, from monthlies to weeklies, or from 30s to 15s, or pages to half pages, and think we’ve gotten the same plan for less money, we’re defying both the market and common sense.”

If Ephron was correct (and he almost always was), why did all of these changes come to be? Mix models usually find that price promotion moves more goods than advertising. It’s hard to get CPG numbers, but a 2000 paper from Ambach & Hess says:

“ … the incremental short-term effect of advertising almost always ranges from just 3% to 6%.”

How is it that the effective advertising that built those iconic brands is only delivering 3% to 6% of sales volume? Could it be that the models themselves are not properly measuring the full contribution of advertising? Could it be that they’re flying without a full set of working gauges? And why should it be an issue for us? Why should we be skeptical?”

Why skepticism?

“True skepticism is the self-correcting mechanism of science.” -- Carl Sagan

Science sometimes gets things wrong. Even medical science has been horribly wrong. If you need some horrendous examples: Goggle “Thalidomide” or “Dr. Alice Stewart and childhood cancer” and you’ll understand what Sagan was talking about. One critical process of science is to provide the skeptical self-correction that keeps science from straying down the wrong path.

If we’re going to call what we do Marketing Science, we should treat it like a “real” science. It should be subject to the open and critical questioning of fellow practicing “scientists.”

The advertising industry is at risk; everyone has lots of skin in this game.

Companies that are not growing the way that Wall Street wants can become targets for extreme cost cutting by their own management or a private equity takeover. Advertisers and all those supplying advertising are at risk, representing tens of thousands of industry jobs.

The opinions and points of view expressed in this commentary are exclusively the views of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of MediaVillage management or associated bloggers.