The Visionaries We Ignored

What follows is an except from a just published book "The 2020s: The Golden Age of Design and Redesign" by Futurist David Houle and Syracuse University Design Professor James Fathers. We were able to get an advance look and thought that Chapter 4, in its entirety might be of interest to you. If you read eBooks, this book is offered at the low promotional price of $2.99 for the next two weeks.

"The earth provides enough to satisfy everyone's need, but not everyone's greed." – Mohandas Gandhi1

"So nature does indeed need protection from man; but man, too, needs protection from his own acts, for he is part of the living world. His war against nature is inevitably a war against himself. His heedless and destructive acts enter into the vast cycles of the earth, and in time return to him." – Rachel Carson 19622

"The modern economist is used to measuring the standard of living by the amount of annual consumption assuming all the time that a man who consumes more is better off than a man who consumes less. A Buddhist economist would consider this approach excessively irrational since consumption is merely a means to human well-being. The aim should be to obtain the maximum of well-being with a minimum of consumption." – EF Schumacher 19683

"When the last tree is cut, the last fish is caught, and the last river is polluted; when to breathe the air is sickening, you will realize, too late, that wealth is not in bank accounts and that you can't eat money." – Alanis Obomsawin 19724

"What you people call your natural resources; our people call our relatives." – Oren Lyons5

"There are professions more harmful than Industrial Design, but only a very few of them. And possibly only one profession phonier: Advertising Design, in persuading people to buy things they don't need, with money they don't have, in order to impress others who don't care." – Victor Papanek 19736

Oh the Voices We Could Have Listened To

The more we have researched this book, the more we have discovered and rediscovered 'voices' from the past whose messages are perhaps more relevant today than they ever were.

Maybe this is because the situation today is more urgent than it ever has been, and maybe because there was a moment of clarity or even sanity in the mid-1960s and early 70s when many people looked ahead and saw the dire implications of our headlong pursuit of growth, ever-increasing consumption and progress at all costs. They spoke up and people listened for a short while, but then they were swayed by the rhetoric of politicians like Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan who claimed that progress and technology were the saviors of all. So the majority put on their blinders to the obvious signs of concern and got back to the neoliberal grindstone.

In a book about design, it is important to note that the majority of these voices weren't from within the design profession, and in many ways that's the point. Designers, ever since they emerged as a profession at the start of the industrial revolution, have aligned themselves with the forces of economic development. The few design voices that cautioned against this were largely vilified and discredited.

R. Buckminster Fuller

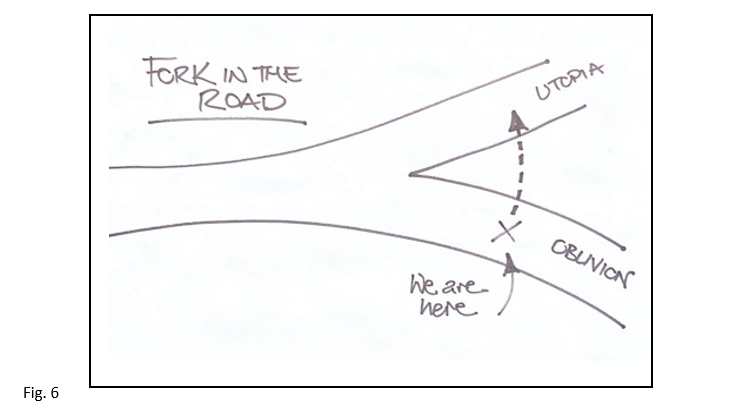

One of the key voices in this period was R. Buckminster (Bucky) Fuller. In 1968 he proclaimed that society had reached 'a fork in the road'-7. Back then he was convinced that 'oblivion' was around the corner. Fifty three years later we are still discussing the same issues and society has blithely continued on its path to oblivion. In fact, many believe we have passed the 'fork' and the only sane action (see the image below) would be to try to forge a path back to the road to 'Utopia'.

In 1965 Fuller declared that the next decade should be dubbed the decade of design and be committed through 'world design' to bringing our way of living and consuming back to operating within the resources of our single planet.8 As we in this book call for a similar focus on the role of design over the next ten years, we take note of the strength of his original call and the resounding apathy that he was met with.

"One hundred years from now, historians will note that in the period of 1927 to 1967 man was so preoccupied and so relatively illiterate that he thought it all right to leave the problems of the world to the politicians. This idea will look preposterous in the perspective of history." – Buckminster Fuller 19629

It is clear that over fifty years later the issues he identified are largely still at play and in some cases markedly worse. For the sake of the planet and the survival of our species, this time we have to do better.

Buckminster Fuller's voice was not alone in calling for a radical shift in the way we live our lives and what our priorities are.

Rachel Carson

In 1962 Rachel Carson, a Marine Biologist and Conservationist, published 'Silent Spring'10 decrying the indiscriminate use of pesticides and their impact on all life forms. 'Silent Spring' is widely acknowledged as one of the key influences in birthing the Global Environmental Movement and in 2006 the book was named one of the 25 greatest science books of all time.11

It is also interesting to note that in her book she prefigures Fuller's 'Fork in the Road' metaphor with a similar one of her own written in 1962 and inspired by Robert Frost's poem 'The Road Not Taken'.

"We stand now where two roads diverge. But unlike the roads in Robert Frost's familiar poem, they are not equally fair. The road we have long been traveling is deceptively easy, a smooth superhighway on which we progress with great speed, but at its end lies disaster. The other fork of the road – the one less traveled by – offers our last, our only chance to reach a destination that assures the preservation of the earth." – Rachel Carson 196212

Robert Kennedy

Carson's work was supported and endorsed by President John Kennedy. This seminal work that sparked the environmental movement for one bright moment in 1968 also inspired the presidential candidate Robert Kennedy. In a campaign speech at the University of Kansas, inspired by Carson's urgent call for change, he made the case that the use of GDP as the primary measure of economic success was fundamentally flawed. His delivery was both inspirational and relatable. In a passage that is even more relevant today, he told the crowd that GDP tallied the wrong metrics. It "measures neither our wit nor our courage, neither our wisdom nor our learning, neither our compassion nor our devotion to our country". He went on to note that it left out the unpaid work of mothers and care givers; it ignored inequality in society; it ignored the health and education of our children, the intelligence of public debate and the integrity of public officials.13 Today we see all of these measures in stark contrast as key indicators of a healthy society. Sadly his voice was snuffed out all too soon.

EF Schumacher

EF Schumacher, an economist and statistician, made a call in the same period for a reconsideration of capitalism and consumption, and the way that Western-style progress and development was being 'prescribed' as the solution to all issues across the globe. In 1964 he wrote an article called 'Buddhist Economics'14, which was influenced by his travels to India and across South Asia, and in particular the Gandhian principles (Swaraj) lived out by the people he met and collaborated with.

He put forward a manifesto for 'optimal' consumption driven by needs as opposed to one of 'maximal' consumption driven by desires. His proposals and the challenges they lay down are even more relevant today and are seen in the trends of minimalism, thrifting and decluttering. In the same way the title of his most famous book, "Small is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered"15 published in 1973, resonates even more today when well-being of people and planet are thrust aside on the rationale of safeguarding profits and the bottom line. In 1995, over twenty years since it was first published, The Times Literary Supplement ranked this book as one of the 100 most influential books published since the Second World War.16

Another aspect of Schumacher's work, the Intermediate Technology movement, is not as well known in the developed West, but has had significant impact in those countries deemed 'less developed'. He defined and championed the deployment of 'Appropriate or Intermediate Technology' as opposed to 'High Technology' approaches in developing economies. His commitment to these ideas resulted in the founding (in 1970) of the Intermediate Technology Development Group (ITDG), an international organization (now called Practical Action) which works across the 'developing world' applying the types of technologies that can be sustained and fully utilized at the local level, "putting ingenious ideas to work so people in poverty can change their world."17

One of the key drivers for this work were failed experiments that involved installing high tech solutions to local problems that, once the Western 'experts' had left, could neither be fully utilized nor repaired when they broke down.

Victor Papanek

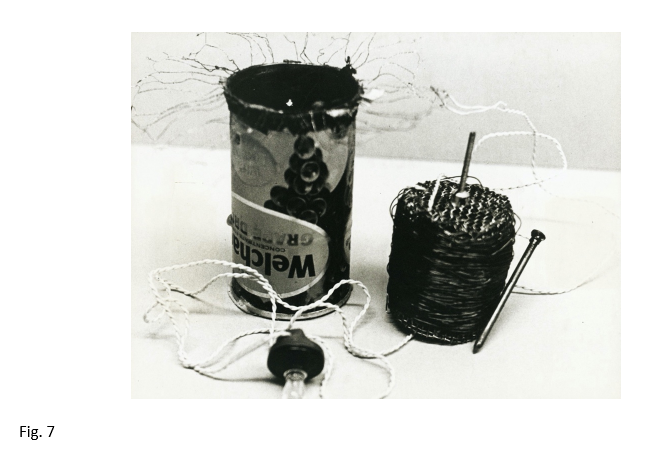

This theme of matching the technology to context is one the key factors at play in the project illustrated below. Victor Papanek was commissioned in 1962 by the US Army to design a radio that could be produced cheaply so that people in remote parts of the world could receive health and educational information via radio.

This radio is perhaps the most famous/infamous project that Papanek worked on and the one he was most vilified for. Why? Because in 1962 it went against every principle of so called progress. This was the age of the transistor radio. Everyone aspired to own a portable radio that blasted out the music of the 60s. In contrast, despite fulfilling the brief in the most efficient and accessible manner, his radio was not sleek or stylish. It cost only 6 cents, was made from an old food can and could be powered by paraffin wax or even dung!18

Since the Industrial Revolution, the Western world had committed itself to the pursuit of progress and profit driven by consumption of the latest products. To suggest, as Schumacher and Papanek did, that technological progress was not the panacea to all ills was heretical and had to be squashed.

In 1996, the Freeplay Radio company19 addressed this same need of providing access to health and educational information to remote locations via radio. They developed a range of 'wind-up' products based on the invention of a 'clockwork radio' by Trevor Baylis. The first models developed were ironically more successful in Western markets, but later, the company developed the 'Lifeline Radio' as a specific response to the originally identified need. The radio by Papanek was cancelled by the military because they feared supplying a microphone for communist propaganda20, the second, over thirty years later, was lauded as a huge step forward in healthcare, and was promoted and funded by governments and celebrities.

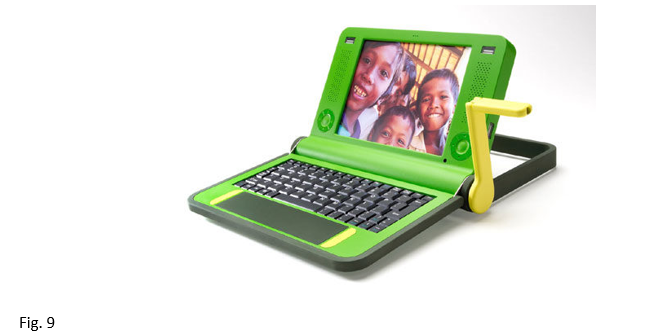

Another example of this is the One Laptop Per Child initiative led by Nicholas Negroponte. Over 15 years after this initiative, it is unclear what impact it had in the world. Three million laptops were produced and distributed (primarily in Latin America) and for a number of years the initiative gained a great deal of attention, but the reality of the project fell prey to its hype. In 2019 Morgan Ames wrote "The Charisma Machine: the life, death and legacy of one laptop per child".21 In this book he lays out some of the triumphs and challenges of this impressive initiative. One of the key challenges with any initiative like this is that technology is moving so fast, especially in the IT and communications sector, it's almost guaranteed to be out of date before it's delivered.

Radio technology is more established, but even in this space smart phones are taking over. Bringing it home and to the present, the issues that Negroponte was citing in 2005 in less developed economies were right in our backyards when the pandemic hit. Children were sitting in fast food drive-throughs to get Wi-Fi access and submitting homework on smart phones because they had no other technology.

Papanek died in 1998 and his legacy lives on as one of the brashest design voices calling for a radical shift in how the profession operated. He worked for the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the World Health Organization (WHO). He called designers 'dangerous', and criticized designs that he saw as tawdry, unsafe and frivolous. As a result, he was shunned by design academics in some of the world's most prestigious institutions.

His book 'Design for the Real World' was translated into twenty three languages and is one of the widest-read books about design. Bucky Fuller was a friend of Papanek and wrote an enthusiastic forward to the first edition of the book. Papanek was ahead of his time in calling for a sharing economy in his book "How Things Don't Work"22, and for designers to be radically human-centered in their work. In "Design for Human Scale"23 he stated that:

"Mass production has turned many manufacturers into latter-day sorcerer's apprentices – unaware of the way a small misjudgment, multiplied a million times, can tatter social coherence."

In his last major work, "The Green Imperative"24 he revisited many of the themes he began to address in "Design for the Real World". Perhaps his most impactful statement in the book is the hopeful and possibly naïve reflection that:

"Perhaps there should be no special category called 'sustainable design'. It might be simpler to assume that all designers will try to reshape their values and their work, so that all design is based on humility."

He went on to say:

"Ecology and environmental equilibrium are the basic underpinnings of all human life on earth; there can be neither life nor human culture without it. Design is concerned with the development of products, tools, machines, artefacts and other devices, and this activity has profound and direct influence on ecology. The design response must be positive and unifying. Design must be the bridge between human needs, culture and ecology."

Both Fuller and Papanek, though advocates for design, were also strident critics of its often unthinking service of capitalist economics and rampant consumerism. Their voices, however, were far from alone.

Vance Packard and Ralph Nader

Vance Packard, a journalist, author and social critic attacked excessive consumption in "The Hidden Persuaders" and how it was driven by psychology in marketing.25 He then went on in "The Waste Makers"26 to attack planned obsolescence and its impact on society.

Packard's hard hitting books were followed in a similar vein by Ralph Nader's exposé of deficiencies in American automobile design. Nader is a lawyer, consumer advocate and environmentalist, who played a key role in the formation of safety legislation in the automobile industry. His book "Unsafe at Any Speed"27, highlighted the 'designed-in' dangers of some cars and his title for Chapter Six, 'It's the Curve that Counts', encapsulates his view that the sole concerns of car designers at that time were stylistic changes and the 'sales curve'. Nader went on to push for safety legislation in many areas including clean water and consumer products as well as championing whistleblower legislation and the formation of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. As part of his activism he made four presidential bids between 1996 and 2008.

The Whole Earth Catalogue

In 1968, Stewart Brand published "The Whole Earth Catalogue".28 It was a fascinating, if short-lived, attempt (50 issues) to place resources in the hands of people who wanted to live a more independent, self-sustaining life… one that was less about consumption and had a lighter ecosystem footprint and supported a regenerative lifestyle. Certain elements of "The Whole Earth Catalogue" include pioneer rhetoric, a celebration of individualism, and a disdain for government and social institutions.

Limits to Growth

In 1970 a group of scientists met to discuss the multiple crises facing humanity and the planet. As a result of that meeting, a team at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) began a study of the implications of continued worldwide growth. The results were published by the newly formed 'Club of Rome' under the title "The Limits to Growth Report".29 50 years later, the club's website states:

"While Limits had many messages, it fundamentally confronted the unchallenged paradigm of continuous material growth and the pursuit of endless economic expansion. Fifty years later, there is no doubt that the ecological footprint of humanity substantially exceeds its natural limits every year."30

The concerns of the Club of Rome have not lost their relevance. This work has been continued since then and a new publication "Post Growth: Life after Capitalism"31 by Professor Tim Jackson is a wonderfully hopeful and inspiring work. It mines history for the fuel to face head-on challenges that must be addressed as a society, as we evolve (because we must) to a post-growth economy. Jackson begins his book with two quotes:

"History, despite its wrenching pain cannot be unlived, but if faced with courage need not be lived again." – Maya Angelou 1993

"Whereof what's past is prologue; what's to come, in yours and my discharge." – William Shakespeare, 1610

It is indeed in our discharge. As we write this chapter, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has released another report on the irreversible damage that we as a species have done to our home planet-32. The report received a great deal of news coverage, and the hope is that we will all begin to listen before it is too late, to carve out a livable existence for all of us.

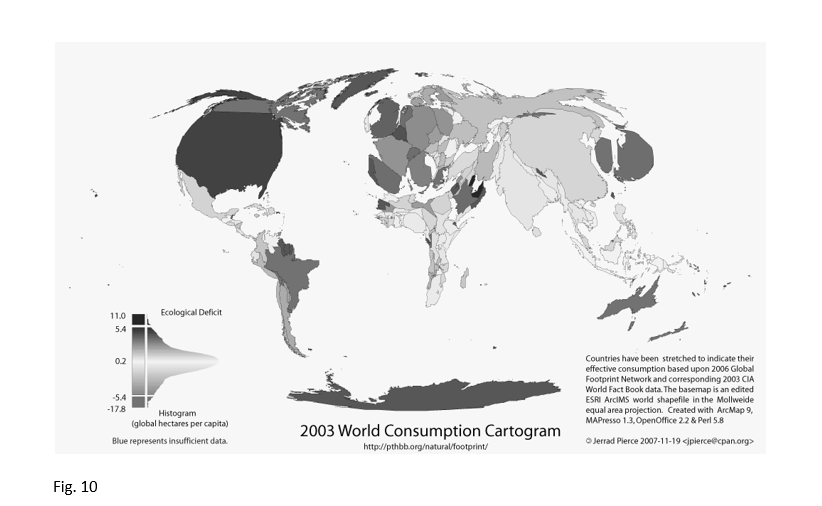

This cartogram produced in 2003, 18 years out of date at the time of this writing, shows the impact of consumption and economic growth, and the places where it is at its most rampant and most impactful to global ecology.

Placed in this context, Fuller's cautions and publications (in particular "The Operating Manual for Space Ship Earth") sit as key narratives in a moment in history which loudly calls for a shift in priorities and practices. Instead, the Western economies have at best wrung their hands and at worst been complicit, as the neoliberal machine has rumbled on crushing people and ecosystems in its wake.

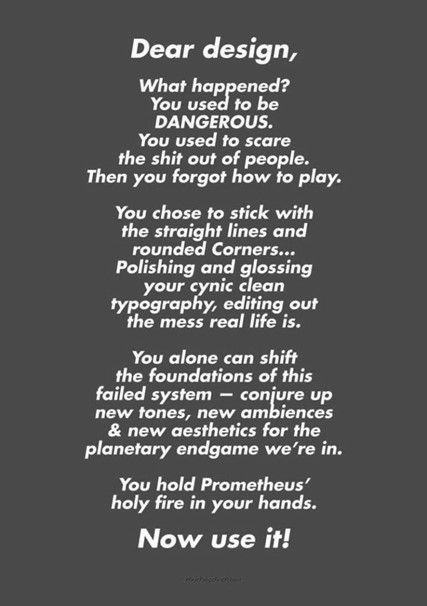

Ken Garland

We will end this chapter with another designer, Ken Garland who in 1963 expressed his concern at the role of designers supporting increasing consumerism. He proposed the 'First Things First Manifesto' at a meeting of the Society of Industrial Artists & Designers. He, along with the other signatories, challenged the graphic design profession to work on projects "worth their skill" as opposed to contributing to the "high pitched scream of consumer selling".

"In common with an increasing number of the general public, we have reached the saturation point in which the high-pitched scream of consumer selling is no more than sheer noise. We think there are other things more worth using our skill and experience on." – Ken Garland 196333

In 2000, the design activist organization 'Adbusters' paid tribute to Garland and revised the manifesto for the new millennium. In 2014 the manifesto was again revised and framed by the statement:

"Many of us have grown increasingly uncomfortable with how the profession's time and energy is used up manufacturing demands for things that are inessential at best."34

Building on this, they launched the First Things First Project. In their explanatory statement they write:

"Over a half-century since Garland's original First Things First Manifesto, and the state of the world remains entrenched in vapid consumerist design. Society has forgotten design's political and emancipatory history."35

If you are a designer and you haven't already signed up to the 2020 Adbusters Manifesto, the link is here: https://www.firstthingsfirst2020.org

The following image is an example of their challenge to the profession.

Click the social buttons to share this story with colleagues and friends.

The opinions expressed here are the author's views and do not necessarily represent the views of MediaVillage.com/MyersBizNet.