"Boston Legal" Broadcast Blast: David E. Kelley vs. the Networks

By Ed Martin TV / Video Download Archives

I’ll miss the unique mix of farcical comedy, challenging drama and cutting social and political commentary that is Boston Legal. ABC will telecast its two-hour finale on Monday, marking the end of a multi-show, multi-network, Boston-based narrative created by David E. Kelley that began in 1997 with ABC’s The Practice, the highly acclaimed series from which Boston Legal was spun-off in 2004. (Attorneys Alan Shore and Denny Crane, played by James Spader and William Shatner, respectively, first appeared on The Practice during its final season, Spader as a series regular, Shatner as a guest star). During its run, characters from The Practice appeared on another series created by Kelley, the legal comedy Ally McBeal, which was telecast on Fox, whilecharacters from Ally McBeal were also seen on The Practice. Later, a character from another series Kelley created for Fox, the high-school drama Boston Public, appeared on Boston Legal.

What a shame that Kelley isn’t ready to roll with a Boston Legal spin-off, if only to keep alive this one-of-a-kind far-reaching franchise (if one may call it that). Given Kelley’s past trajectory, it need not even be on ABC. In addition to Fox, Kelley has a rich history at NBC, where he worked as a writer and producer on L.A. Law, and CBS, which telecast his quirky small town drama Picket Fences.

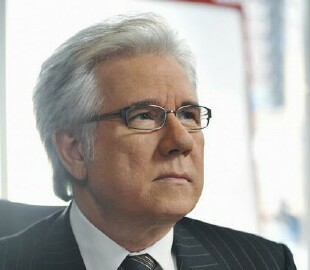

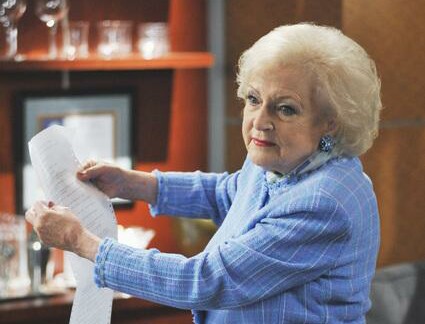

Kelley has never been one to keep his opinions to himself, or out of the scripts for his shows – especially when the topic is television itself. Last week’s penultimate episode of Boston Legal made that abundantly clear, in a storyline that began with a very frustrated Catherine Piper (a recurring character played by Betty White) expressing to Attorney Carl Sack (John Larroquette) her outrage at being made to feel so useless and unwanted during her senior years. She wanted to file a suit against someone or something, and broadcast television was one of her suggested targets.

“We’re just shoved aside as a nuisance,” Catherine declared. “I can’t even watch television shows for God’s sake, because the networks consider me irrelevant. It seems they don’t program for anyone over 50!” (These words took on a sublime glow coming from the mouth of Ms. White, at 86 a beloved broadcast television legend whose career in the medium spans seven decades.)

“You actually may have something there,” Sack replied. “The networks are supposed to serve the public. I’m over 50 myself and I want something to watch!” With that, the stage was set for several scenes that took broadcast television to task for failing to meet its obligations while continually narrowing its focus on ever-younger viewers to the detriment of the overall audience, not to mention the business itself. Youth-obsessed advertisers were briefly referenced but otherwise spared.

After his meeting with Catherine, Sack presented his argument to Judge Clark Brown (Henry Gibson), who responded with characteristic exasperation, “You can’t sue the networks!”

Sack was undeterred. “The airwaves, judge, are a public trust, at least as far as the broadcast networks are concerned,” he explained. “That’s why they’re regulated.

“There may have been a time when it didn’t make practical business sense to exclude the old, but not today,” Sack continued. “Americans over 50 make up the fastest growing market . . . The baby boomers, now all over 50, earn two trillion in annual income . . . We’ve got more money. We spend more money. We watch more television. We go to more movies. We buy more CDs than young people do. And yet, we’re the focus of less than ten percent of the advertising. All the networks want to do is skew younger. Kids shows for kids! The only show unafraid to have its stars over 50 is Bo . . .” (Here Sack pointed directly to the camera.)

“I can’t say it,” Sack sighed. “It would break the [fourth] wall!”

Brown roared again. “You can’t tell the networks what shows to make!” he cried.

“No, but you can order them not to discriminate!” Sack replied. “What they’re doing intentionally excludes a class of society. That’s bigotry! We should be able to turn on our damn televisions and see something other than reality shows aimed at fourth graders, game shows aimed at those slightly smarter than fifth graders and scripted shows with dimwitted, sex-crazed twenty-somethings running around in suits or doctors’ scrubs! Old people, the ones with intelligence, don’t want to watch that crap! We’re fed up! The networks might think we’re dead, but we’re not. We’re very much alive, with working brains! Give us something to watch, damn it!”

Sack continued his pitch to Judge Brown during their lunch break.

“You know, judge, in addition to there being little for us to watch, most of it stinks,” he said. Sack then brandished his cell phone. “It’s this thing’s fault! A lot of people are on it while they’re watching. They no longer give television their undivided attention. They’re on the phone, or texting, or on the Internet. So the producers, they dumb down the plots, make them easier to keep up with while their viewers multi-task. Kids nowadays watch an average of three hours of television a day. That’s while being distracted. People over 55, we watch six hours a day. And we really watch. So, why aren’t they programming for us? Do these idiots a favor, judge. Send these network bozos a clue!”

Later, an angered Judge Brown addressed the courtroom. “Ageism is one of the last socially condoned bigotries, and it is rampant in this broadcast network business,” he hissed. “They consider those of us over 50 to be irrelevant! How is it possible that we are not even part of the target demo when we watch the most television and spend the most money? My God, there are 87 million of us, and that number will grow by 31 million more by 2020. Are you really telling me that it doesn’t make sense to make television shows that we want to watch? If I am to assume that the industry is not run by a bunch of idiots, then I can only conclude that it is dominated by prejudice! The case stands.”

Okay, so maybe certain aspects of Kelley’s – I mean Sack’s – argument are outdated, or seem to come from someone who is too busy making television to really watch it. Primetime broadcast programming isn’t all bad, though it might seem somewhat lopsided to anyone who doesn’t have an insatiable hunger for procedural crime dramas. Sadly, with Boston Legal reaching the end of its run we’ll never see this case argued.

Before the end of the same episode, Kelley seemingly took a direct shot at ABC. Attorneys Alan Shore and Denny Crane were shown enjoying their nightly cocktail hour on the terrace outside their offices, discussing their next challenge: A return to the Supreme Court, this time to argue in favor of allowing Alzheimer’s patients access to drugs that are known to slow the progress of the disease but are not yet approved by the FDA. That high-stakes showdown will be the primary storyline in next Monday’s two-hour series finale.

“Hey, maybe I’ll retire after this,” Crane mused, cigar in hand. “What better way to go out? My last case, in front of the Supreme Court. Now there’s a finale!”

“They should put it on TV,” Shore responded.

“They’ll get ratings!” Crane agreed.

“If they promoted us,” Shore replied. “Of course, I think there’s a law against promoting us.”

“Seems to be,” Crane concluded.

Television won’t be the same without these guys.