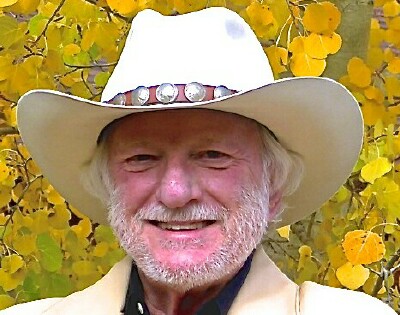

"The Revolutionary Evolution of the Media" -- Chapter 4, Part 1 -- Paul Maxwell

Chapter 4 -- In Print

Before Johannes Gutenberg and his apprentices, there was paper and there was woodblock duplication of carvings. Though the Chinese had invented it much earlier, paper rather slowly made its way to Europe via the Silk Road and then across Northern Africa. Crusaders also “discovered” it and some samples made it to Rome.

Paper was introduced into Muslim Europe (the Iberian peninsula of Spain and Portugal) and Sicily around the 11th Century … paper made its way slowly into first Italy and Southern France and then by the 15th Century into Germany and Flanders. A mid-level merchant in Prato, Italy named Francesco Datini left a trove of, no kidding, 126,000 pieces of business correspondence. Datini had branch offices in Pisa, Genoa, Majorca and in Spain. He died childless leaving his property to the local poor … who saved it all.

Of course, before paper per se, other forms of raw materials were utilized to produce scrolls, books and pamphlets in limited quantities. Papyrus, parchment, vellum, palm leaves and certain kinds of bark were utilized. Of course, these didn’t exactly encourage mass distribution; that wouldn’t happen until the advent of paper. The first mechanized paper mill was founded in Leiria, Portugal around 1411 using waterpower. Papermaking spread throughout Europe in great volume in less than a century.

Paper was first used in commerce, of course. Cheaper than other forms some of the first paper was used for inventory and bills of laden. The next step was filing it all, which has left clear commercial records found in Bruges, London, Venice, Cologne and Florence. Wool, cloth, silk and trinkets such as the mirrors made by Gutenberg before he figured out printing were tracked until sold.

Gutenberg and his moveable type, modified wine press and oil-based ink (unique at that time to him) were demonstrated at the Frankfurt Fair in 1454 showing off trial pages of the Bible (in Latin in the Vulgate version) printed on high quality paper from Italy. Gutenberg tried to monopolize printing by keeping some of what he did secret. That didn’t work. Craftsmen all over Europe were printing books and selling them within months.

One might have expected to see quick growth from printing books (which took awhile) to printing broadsheets with news. But that didn’t happen right away. Instead, the printing of books took off.

In the early history of books, religious texts led the way … and made a whole lot of churchly big wigs spitting mad as they thought that only the holy (themselves) should have access to holy texts. Governments and the rich elite got in the act too with their own special books and pretty soon books were appearing in the vernacular as opposed to Latin or Greek.

That didn’t mean a whole lot for the new class of printers who found that while books could be printed they weren’t often bought. Most of the early movers in fact, in fact, didn’t last long either simply abandoning their print shops or going bankrupt.

Distribution via bookstores hadn’t yet developed. Individually marketing books was tried to institutions but, still, not many bought. The market for manuscripts turned out to be limited.

Oddly, news wasn’t immediately thought of as a market. No one printed stories about the fall of Constantinople or much else for 30+ years until siege of Rhodes in 1480 when the threat of further encroachment by Turkish troops prompted the Pope’s appeal for help to be printed and distributed. Most news still moved as correspondence carried by couriers plus gossip by travelers.

The first big customer of the fits and starts growing printing industry was, contrary to its earlier objections, the Church. Contracts were let to produce prayer books, psalters, sermon collections and, most importantly with future ramifications, indulgences. Nothing like a reliable institutional customer.

In Rome in 1472, the printers Konrad Sweynheim and Arnold Pannartz were struggling. They had printed too many sheets – 20,000 – and couldn’t sell them. So they appealed to the Pope.

Meanwhile, governments became the second big customer group with attempts to mechanize many aspects of actual governing. Publicizing decisions of officialdom would become more important as governments figured out publicity.

But the Church provided the best bet.

The theology of salvation had grown into a business. A big business. In exchange for the performance of pious acts including contributions to the Church, a pilgrimage or contribution to a Crusade, the repentant was guaranteed a shorter stay in purgatory of so many days depending upon the act or contribution (40 days usually). The repentant was even given a certificate which initially was handwritten on parchment or paper specifying the number of days.

It didn’t take long for the Church and the growing printing industry to figure out pre-printed indulgences could save a lot of time. Easy to print, not many words and blanks for the seller to simply fill in. Nice business. Some scholars think as many as four million indulgence certificates were printed. In this case, the Church handled the distribution, too.

Some 28,000 printed texts from the first era of printing from the 15th Century have survived including some 2,500 broadsheets of which some 800 or so are indulgences. Books were usually printed and bound in runs of 300 to 500. One old invoice for indulgences ordered 20,000 copies.

One Cardinal Raymond Peraudi ran three major fund-raising efforts in Northern Europe between 1488 and 1503 asking for contributions for both the Church and local officials. These early efforts sort of set the groundwork for today’s political and religious campaigns. They featured advance men, pamphlets and broadsheets heralding the preacher’s arrival plus sermons and indulgences for sale upon his arrival followed by more broadsheets touting his visit. Peraudi had imitators all over Northern Europe.

The effects of the printed materials were not lost on others.

Next week: Chapter 4, Part 2 -- More in Print

In an almost 50-year career writing and reporting on media, Paul S. Maxwell started and/or ran some 45-plus publications ranging from CATV Newsweekly to Colorado Magazine to CableVision to Multichannel News to CableFAX and The BRIDGE Suite of daily newsletters and research publications. In between publishing stints, Maxwell served as an advisor and/or consultant to a number of major media companies and media start-ups including running a unit of MCI and managing a partnership of TCI and McGraw-Hill.

Send any and all criticisms, suggestions, rants, threats, corrections, etc. to him at cablemax@mac.com. He has a new Web site coming soon!

Check us out on Facebook at MediaBizBloggers.com

Follow our Twitter updates at @MediaBizBlogger

The opinions and points of view expressed in this commentary are exclusively the views of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of MediaBizBloggers.com management or associated bloggers. MediaBizBloggers is an open thought leadership platform and readers may share their comments and opinions in response to all commentaries.